Table of Contents

What Is Venture Capital? Funding Innovation and High-Growth Companies

- CLFI Team

- 6 min read

Venture Capital (VC) is a form of private equity financing that provides funding to early-stage, high-potential companies in exchange for ownership stakes. Venture capitalists supply not only capital but also expertise, networks, and governance oversight, helping young businesses scale rapidly. VC is central to the startup ecosystem, fuelling innovation in technology, healthcare, and other sectors where traditional financing is often unavailable due to high risk.

Venture capital is examined within the broader spectrum of private equity, including the different types of private capital and their role in funding high-growth companies, as covered in the Private Equity Course Modules.

Table of Contents

- What Is Venture Capital?

- Stages of Venture Capital Financing

- How Venture Capital Works

- Valuation in Venture Capital

- Benefits and Risks of Venture Capital

- Case Study: Facebook and Accel Partners

- Further Reading

What Is Venture Capital?

Venture capital is financing provided by specialised funds to startups and emerging businesses with strong growth potential but limited operating history. In return, investors receive equity stakes that can become highly valuable if the company succeeds. Unlike bank loans, VC is not repaid in cash but through eventual “exits,” such as an Initial Public Offering (IPO) or acquisition. This makes venture capital both high risk and high reward.

Think of a team launching a company to disrupt urban mobility with electric scooters connected through a smartphone app. The idea could transform transport in cities, but at the outset there are no steady revenues, let alone profits. Walk into a traditional bank, and the first thing the loan officer will ask for are years of financial records—proof that you already generate earnings and can cover interest and repayments. That works for established businesses but not for disruptive startups that need capital to prove their concept in the first place.

This is where venture capital enters. VC funds are designed to provide the early backing banks won’t, taking equity stakes and shouldering the risk that many ventures will fail. Where lenders want to see positive EBITDA before committing money, venture capitalists accept the uncertainty, aiming for outsized returns from the few companies that succeed spectacularly.

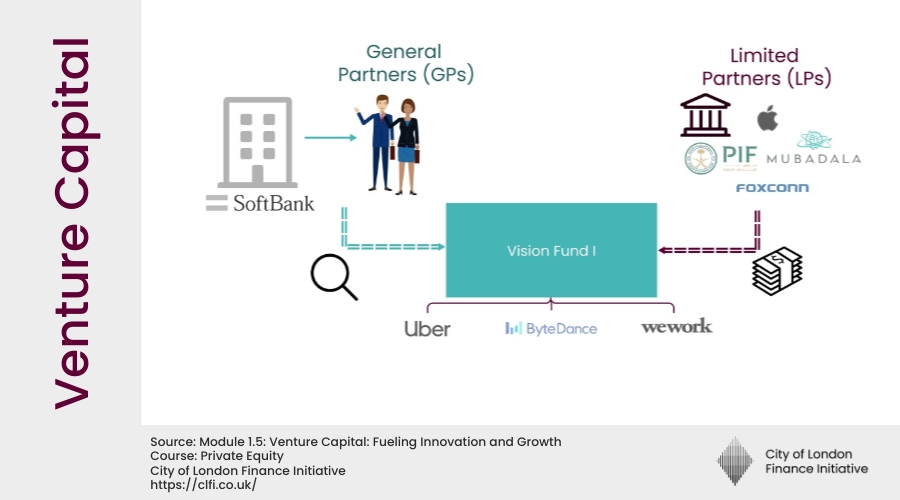

How Venture Capital Works

Venture capital is structured through limited partnerships. General Partners (GPs) manage the fund, raise capital from investors, and make investment decisions. Limited Partners (LPs)—such as pension funds, endowments, and high-net-worth individuals—provide the capital. GPs earn management fees and a share of profits (known as carried interest), while LPs receive returns if portfolio companies exit successfully.

Once invested, VCs actively support portfolio companies. They may take board seats, introduce clients, or advise on strategy and governance. Their influence can be decisive in helping startups professionalise and grow quickly enough to justify valuations.

Programme Content Overview

The Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance delivers a full business-school-standard curriculum through flexible, self-paced modules. It covers five integrated courses — Corporate Finance, Business Valuation, Corporate Governance, Private Equity, and Mergers & Acquisitions — each contributing a defined share of the overall learning experience, combining academic depth with practical application.

Chart: Percentage weighting of each core course within the CLFI Executive Certificate curriculum.

Capital Is a Resource. Allocation Is a Strategy.

Learn more through the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance – a structured programme integrating governance, finance, valuation, and strategy.

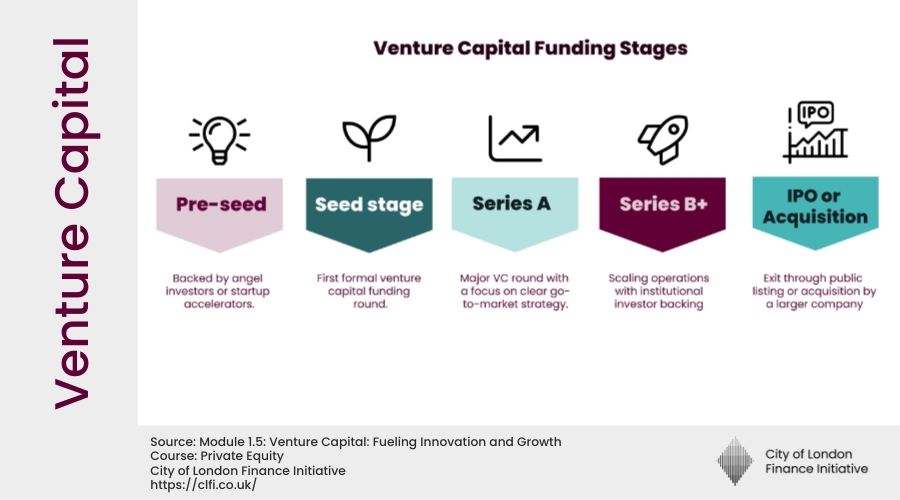

Stages of Venture Capital Financing

Startup funding rarely happens all at once—it progresses through stages as the business develops. Each stage brings new types of investors, higher valuations, and different expectations for governance.

The table below summarises the main steps:

| Stage | Description | Typical Investors | Valuation & Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|

| Friends & Family (Seed 1) | Initial funding from close personal connections, used to cover very early expenses like prototypes or basic product development. | Friends, family, trusted associates | Example: $50K for 5% at ~$1M valuation |

| Accelerator / Incubator (Seed 2) | Early programmes that combine capital with mentorship and networks, often a springboard to further funding. | Y Combinator, Techstars, Launch, etc. | Typical example: $125K for ~7% ownership |

| Seed Round (Seed 3) | Raised after accelerators to scale early operations and validate the model further. Often led by angels or seed-focused VCs. | Angel investors, early-stage VCs | Valuations often rise toward ~$5M |

| Seed Extension (Seed 3+) | Additional capital raised if more runway is needed before Series A. Usually adds capital without significantly raising valuation. | Existing backers or new angels | Valuation often unchanged, capital “topped up” |

| Series A | The first major VC round. Typically involves governance rights like board seats and sets the foundation for structured growth. | Venture Capital funds | Valuations typically $10M+ |

| Series B / C / D | Later funding rounds aimed at scaling globally, entering new markets, or funding acquisitions. Governance and investor oversight expand further. | New or existing VC funds, growth equity investors | Valuations rise 10–20% per round, depending on performance |

Valuation in Venture Capital

Valuing startups is fundamentally different from valuing established companies. Traditional methods—such as price-to-earnings ratios—depend on stable revenues and profits. Startups usually have neither. Venture capital therefore relies on approaches that balance limited current data with assumptions about future potential. Valuation is less about what the company is today, and more about what it could become if it achieves scale.

- Pre-money and post-money valuation: Every round is priced by negotiation. The pre-money valuation is the company’s value before the new capital is invested; the post-money valuation adds the investment amount. For example, a €10 million pre-money valuation with a €2 million investment produces a €12 million post-money valuation. This sets the ownership percentages of founders and investors going forward.

- Comparable transactions: Startups are often benchmarked against other young companies that recently raised funding. Multiples may be based on revenues, users, or other traction metrics. This method provides an “anchoring” effect—investors look at what the market has paid for similar risk profiles.

- Venture Capital Method: This approach starts with an assumed exit value (for example, IPO or sale in five years) and then discounts it heavily using high rates (30–60% or more). The logic is simple: only a few startups succeed, so the winners must return enough to offset the failures in a VC portfolio.

- Risk-adjusted multiples: In some cases, investors apply conservative multiples to current revenues or users, explicitly adjusting for execution risk. For example, a SaaS startup with €1m recurring revenue may be valued at 5× (€5m), whereas public peers trade at 10×. The discount reflects the uncertainty of survival and growth.

Ultimately, startup valuation in VC is part numerical estimations, part narrative. Numbers provide a framework, but investor sentiment, founder credibility, and competitive dynamics often shape the final figure as much as the spreadsheet does.

Benefits and Risks of Venture Capital

The main benefit of VC is access to substantial capital and strategic expertise that enables rapid scaling. For entrepreneurs, it provides the resources needed to compete in fast-moving markets. For investors, successful deals can deliver extraordinary returns, sometimes exceeding 10× the initial investment. However, risks are equally high: many startups fail, meaning VCs rely on a small number of “home runs” to generate fund-level returns. Dilution, loss of control, and pressure for rapid growth are also common concerns for founders.

Case Study: Ben & Jerry’s – When Capital and Governance Collide

Ben & Jerry’s began in 1978 as a small Vermont ice-cream shop with a mission that blended business success with social responsibility. Early investors backed both the company’s commercial potential and its values-led approach, providing capital that helped it scale into a household name across the United States.

In 2000, the business was acquired by Unilever for $326 million. The deal included a unique arrangement: an independent board was established to safeguard the brand’s social mission even under corporate ownership. This structure highlighted a key governance innovation, but it also exposed tensions when activism and social advocacy clashed with the financial and reputational priorities of the parent company.

The governance caveat: accepting outside investment means giving up more than shares—it often involves giving up influence. Venture capitalists and corporate acquirers typically secure board seats, voting rights, or other governance levers that can shape strategy. At Ben & Jerry’s, disagreements between the independent board and Unilever came to a head in 2025, when the brand’s CEO was removed after refusing to dilute the company’s tradition of outspoken advocacy. The board responded by filing suit, claiming the dismissal violated the original merger agreement.

This episode highlights an important caveat for founders and boards seeking outside funding: they must carefully assess whether prospective financial backers are aligned with the organisation’s mission and values. In a sector where groupthinking dominates, capital can come with implicit expectations that run counter to a company’s social or ethical commitments. This is why in corporate governance a diverse board is encouraged—not as a box-ticking exercise for DEI statistics, but as a safeguard against the pedigree-driven groupthinking that still defines too many boardrooms. Diversity of perspective is a structural defence, ensuring that capital does not silence values but enables them to scale responsibly.