Table of Contents

What Are SPACs and How Do They Work?

- CLFI Team

- 9 min read

A Special Purpose Acquisition Company, or SPAC, is a listed shell company that raises money through an IPO and then seeks a private business to acquire. Investors back the SPAC’s sponsor team, and if a suitable acquisition is approved, the private company becomes public through the merger rather than a traditional IPO.

Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs), sometimes called blank cheque companies, offer an alternative route to public markets. Instead of an established business going public to fund growth, investors first buy into a cash shell, and the operating company appears later when the shell acquires or merges with a private target.

In practice, a SPAC IPO creates a pool of capital with no operations of its own. The sponsor team then searches for a promising private business and negotiates a merger that effectively turns that business into a listed company. This structure has attracted interest in the United States and the United Kingdom as a kind of reverse IPO, promising speed, flexibility, and access to prominent sponsors.

For readers exploring SPAC examples, looking through a list of Special Purpose Acquisition Companies, or trying to understand what SPAC structures mean for investors and executives, this article provides a step-by-step overview of how SPACs work, why they surged in popularity, and the main risks to valuation, governance, and long-term performance.

Table of Contents

- What Is a SPAC?

- How Do SPACs Acquire Companies?

- How Are SPAC Sponsors Incentivised?

- Why Did SPACs Become So Controversial?

- How Do Governance and Voting Rights Work in SPACs?

- What Are the Valuation and Regulatory Risks?

- Further Reading

What Is a SPAC?

A Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is a publicly traded shell company formed with the specific objective of acquiring or merging with a private business. At launch it has no commercial operations. It raises funds through an IPO, typically at around $10 per unit, from institutional and retail investors, and places those funds in a trust account while the sponsor team searches for a suitable target.

Definition

Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC)

A SPAC is a listed shell company that raises money from investors through an IPO and then seeks to acquire or merge with a private business, which becomes public through the transaction instead of a traditional IPO.

In summary, a SPAC typically has the following characteristics:

- Formed as a cash shell with no operating business.

- Raises capital through an IPO and places proceeds in a ring-fenced trust account.

- Led by sponsors, often investors, private equity professionals, or industry executives.

- Has a fixed period, usually 18 to 24 months, to complete a merger with a private company.

- Returns funds to shareholders if no suitable business combination is completed in time.

Investors in a SPAC therefore bet on the sponsor’s skills and network. If the team succeeds in identifying and negotiating an attractive deal, early SPAC investors may benefit from access to a high-growth company at an earlier stage than they could reach through a conventional listing process.

How Do SPACs Acquire Companies?

After the IPO, the sponsor team works within a defined timeframe to identify a private company that fits the SPAC’s investment thesis. Merging into a SPAC is often described as a faster route to public markets for the target, yet it still requires extensive negotiation, regulatory disclosure, and shareholder approval.

- The SPAC evaluates potential targets, conducts due diligence, and negotiates valuation and deal terms.

- Once a target is selected, the SPAC announces a proposed business combination, often called the de-SPAC transaction.

- Shareholders receive detailed information comparable to a traditional IPO prospectus.

- Investors vote on the transaction and may redeem their shares for cash if they prefer not to stay invested.

- If approved, the SPAC and the private company merge, and the combined entity becomes the new listed company.

To support the acquisition, SPACs frequently raise additional capital through a Private Investment in Public Equity (PIPE) transaction, where institutional investors commit new funds in exchange for shares, often at an agreed price level. This top-up capital can be critical when the target is significantly larger than the SPAC’s original cash pool.

| Feature | Traditional IPO | SPAC Route |

|---|---|---|

| Who goes public? | Operating company | Cash shell first, operating company later |

| Timing | Longer preparation and book-building process | Often faster from agreement to listing |

| Price discovery | Market-driven at IPO | Negotiated between SPAC, target, and PIPE investors |

| Investor protections | Standard prospectus and listing rules | Prospectus-style disclosure plus redemption rights |

For example, Arrival’s listing in 2021 involved a merger with the SPAC CIIG Merger Corp and additional commitments from institutional investors such as Fidelity, BlackRock, and BNP Paribas Asset Management to support the UK electric vehicle maker’s debut on the Nasdaq exchange.

Consider a simplified capital structure. A SPAC raises $100 million in its IPO and identifies a private technology company valued at $7 billion. To close the transaction, it secures an additional $400 million through a PIPE. After shareholder approval, the combined company lists with access to $500 million in new capital on a post-money valuation of roughly $7.5 billion.

In this scenario, the new money investors receive around 6.67 percent of the combined equity in exchange for their cash, with approximately 1.33 percent held by SPAC shareholders and 5.33 percent by PIPE investors, in line with their contributions. Founders and early backers of the technology company still own most of the business but accept some dilution in order to gain capital and a public listing.

How Are SPAC Sponsors Incentivised?

SPAC sponsors are usually compensated through a structure known as the promote. This typically grants them up to 20 percent of the post-IPO shares for a nominal outlay, for example around $25,000. These founder shares convert into ordinary stock when a merger completes. The design rewards sponsors for sourcing and closing a transaction.

After the 2020–2021 boom, critics argued that this model can encourage completion of deals rather than careful selection of high-quality targets. Sponsors share in upside if any transaction occurs, yet they have limited direct downside if the post-merger company underperforms. To rebalance incentives, some recent SPACs have introduced earn-out clauses, where part of the sponsor’s promotion vests only if the share price meets specific performance triggers over time.

Key takeaway: promote economics can distort decision-making if they are not carefully structured, and may misalign sponsor incentives with the interests of long-term public shareholders.

Why Did SPACs Become So Controversial?

During the COVID-19 lockdown period, SPACs rose to extraordinary prominence. Traditional capital markets were unsettled, risk appetite returned quickly, and the SPAC model appeared to offer a quicker, more flexible path to listing, often led by high-profile sponsors. For a time this was described as a new wave of financial innovation in public markets.

Retail investors, sometimes trading stimulus-era savings, bought shares in SPACs largely for the chance that a deal announcement might push prices higher. It became increasingly common to purchase almost any listed SPAC ahead of a potential transaction, a pattern that resembled meme-stock behaviour but layered on top of more complex financial structuring.

Public attention grew further as celebrities and public figures, including Shaquille O’Neal, Alex Rodriguez, Paul Ryan, and Chamath Palihapitiya, launched SPACs in series, sometimes without naming a specific target. Marketing emphasised track records and personal brands rather than detailed information about future acquisitions, which made it harder for less experienced investors to judge risk and value.

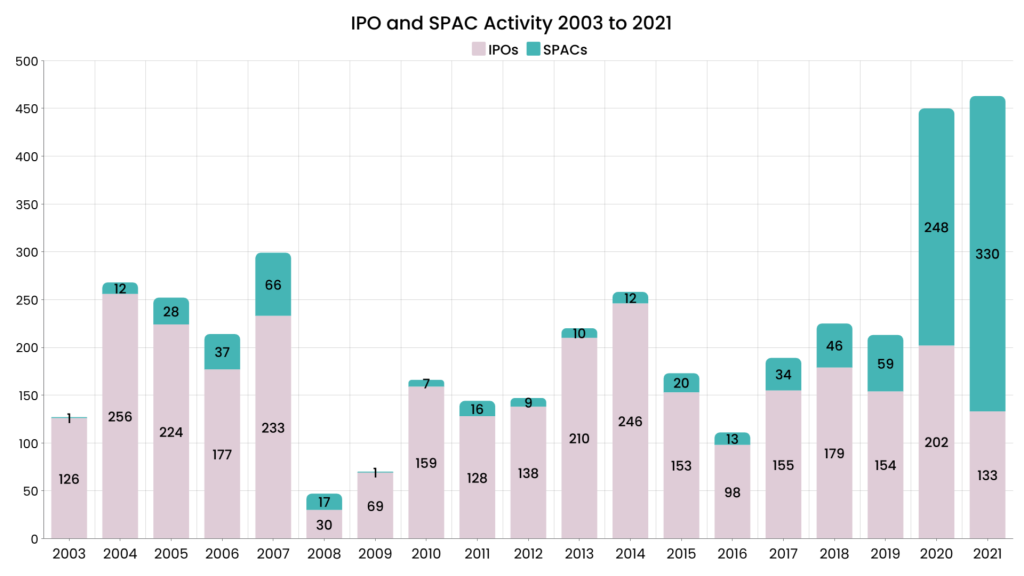

Source: CLFI analysis of public IPO and SPAC listing data.

Many SPAC structures gave sponsors significant participation in future gains while passing much of the economic risk to public investors. Sponsors often received large ownership stakes in return for small initial investments, regardless of how the combined business performed after the merger. What had been presented as broader access to private-market opportunities sometimes left long-term shareholders exposed to weak alignment and limited downside protection.

The experience of Pershing Square Tontine Holdings (PSTH), the SPAC launched by Bill Ackman, illustrates these tensions. PSTH raised around $4 billion, making it one of the largest SPACs at the time, yet it did not complete a merger and ultimately returned capital to investors. Attempts to structure a stake in Universal Music Group encountered regulatory objections, and exploratory discussions with companies such as Airbnb and Stripe did not progress to a completed transaction.

As markets stabilised and strong private companies regained access to traditional listings, the perceived advantages of SPAC structures diminished. PSTH has become one of the most visible examples of a high-profile SPAC that did not reach a merger stage, and it highlights how even well-resourced sponsors can face structural, regulatory, and timing constraints that limit the model’s effectiveness.

How Do Governance and Voting Rights Work in SPACs?

One distinctive feature of SPACs is the degree of control available to investors before a merger completes. Shareholders vote on whether to approve the proposed acquisition, and they can choose to redeem their shares and recover their original investment, plus interest, regardless of how they vote. This redemption mechanism is designed to limit downside risk for public investors.

SPAC boards typically include independent directors, yet governance practices vary widely. Some structures closely mirror the expectations for listed companies, with clear committee responsibilities and conflict-of-interest policies. Others rely heavily on the sponsor’s judgement, which can increase the importance of transparent disclosure and robust independent challenge.

Supervisory bodies such as the US Securities and Exchange Commission have increased scrutiny of SPACs, especially around disclosure quality, forward-looking projections, potential conflicts, and outcomes after the de-SPAC transaction. Once the merger completes, the combined company operates under the usual corporate governance framework, including audit oversight, board committees, and ongoing reporting obligations.

What Are the Valuation and Regulatory Risks?

Valuation in SPAC transactions commonly relies on forward-looking projections, particularly in high-growth sectors such as technology or electric vehicles. This can make due diligence more demanding and increases the likelihood that post-listing performance diverges from expectations. Several SPAC-backed businesses have experienced sharp share price declines when forecasts proved difficult to achieve.

Regulators have responded with proposed guidance that seeks to align SPAC disclosure and liability more closely with traditional IPO standards. This includes closer review of projections, incentive structures, and the role of underwriters and advisers. For both investors and founders, understanding these developments is essential before committing to a SPAC route.

In practice, boards, executives, and investors assessing a SPAC opportunity need to look beyond headlines and focus on governance quality, sponsor incentives, dilution, and valuation assumptions. The SPAC framework can provide a practical route to listing for some companies, yet its benefits depend on disciplined deal selection, transparent communication, and a clear alignment between insiders and long-term shareholders.

Learn more in the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance .

Further Reading

From CLFI Insight and Resources

Programme Content Overview

The Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance delivers a full business-school-standard curriculum through flexible, self-paced modules. It covers five integrated courses — Corporate Finance, Business Valuation, Corporate Governance, Private Equity, and Mergers & Acquisitions — each contributing a defined share of the overall learning experience, combining academic depth with practical application.

Chart: Percentage weighting of each core course within the CLFI Executive Certificate curriculum.

Grow expertise. Lead strategy.

Build a better future with the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance.