Table of Contents

How to Value Your Business to Private Equity

- 8 min read

Selling to Private Equity: How Valuation Really Works

For executives, family offices or business owners preparing to engage with private equity, valuation is the entry point to any negotiation. Whether raising growth capital, considering a buyout, or exploring an eventual exit, understanding how private equity investors assess value is essential. Unlike the public markets, where share prices fluctuate daily and provide a live benchmark, private equity operates in a less transparent environment. Valuation here is not a single number but a process of estimation, judgment, and negotiation.

The International Private Equity and Venture Capital Valuation Guidelines (IPEV Guidelines) describe valuation as both an art and a science. Quantitative models provide the scaffolding for valuation, but numbers alone do not dictate the final outcome. In practice, professional judgment fills in the gaps — and those gaps are often wide when dealing with private businesses.

In public markets — think of quoted shares like Apple or NVIDIA that you can track in real time — investors see a price signal every day. In the private market, no such live indicator exists, leaving valuation to be inferred from financial data, transactions, and professional judgment. So, information is harder to come by, ownership is often concentrated in the hands of a few individuals, and financial reporting may lack the depth or consistency that investors expect from listed firms. All of this means that valuation is never a purely mechanical exercise. The figure attached to a business can shift depending on why it is being valued, when in the cycle it is assessed, and who is making the assessment. For executives and business owners, the lesson is that valuation is not an absolute truth but a negotiated estimate shaped by both data and context.

Private Equity Valuation Methods Explained

Because valuation is shaped as much by context as by calculation, private equity firms do not rely on a single formula. Instead, they turn to a small set of established methods, selecting the approach that best fits the maturity of the company, the sector it operates in, and the circumstances of the transaction.

Understanding these methods allows CEOs and owners not only to anticipate how investors may view their company, but also to shape a more compelling narrative about its potential.

A common starting point is to look at the price paid in the most recent investment round. If outside investors have just put money into the company, their valuation provides a useful reference for what the business may be worth today. This benchmark can carry weight for a period of time, especially if the deal was recent. However, its relevance quickly fades if market conditions change or if the company’s performance begins to move away from what those investors originally expected. The recent history of OpenAI illustrates this point vividly. In just over a year, the company’s value swung from around $30 billion in early 2023 to $86 billion a few months later, then to $157 billion in late 2024, before doubling again to $300 billion by March 2025. These dramatic shifts show how the “price of recent investment” can anchor valuation in the short term, but also how quickly that anchor can move when investor sentiment and growth expectations evolve.

From here, many private equity professionals turn to comparable multiples. This method benchmarks a company against peers — whether listed public firms or other private transactions — using shorthand ratios such as Enterprise Value to EBITDA or revenue. While this approach offers quick relatability, the art lies in choosing comparables that truly match. Differences in scale, growth trajectory, or risk profile can make a surface-level comparison misleading, requiring careful adjustments to avoid over- or under-valuing a business.

For companies whose worth is tied more closely to tangible holdings, net asset value provides another lens. By adjusting the balance sheet to reflect the fair market value of assets and liabilities, this method offers a conservative but firm floor for valuation. It is especially relevant in asset-intensive sectors like real estate or infrastructure, where earnings may fluctuate but asset backing remains central.

Where future growth and cash generation are in focus, the discounted cash flow (DCF) model comes into play. DCF projects expected free cash flows and discounts them to today’s value using an appropriate cost of capital. Its comprehensiveness is appealing, but its sensitivity is also its weakness: small shifts in growth assumptions, margins, or discount rates can dramatically alter the outcome. This makes credibility of forecasts a critical factor.

Finally, many valuers round out their analysis with industry benchmarks and scenario testing. Sector-specific measures — such as subscriber counts in telecoms or reserves in energy — provide contextual anchors, while scenario analysis tests how valuations move under different market conditions. Rising interest rates, sudden input cost increases, or regulatory shifts can all be modelled to show how resilient (or vulnerable) the valuation really is.

EBITDA: The Cornerstone Metric

While several valuation methods exist, one metric dominates in private equity: EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization). Investors use EBITDA as a proxy for operational cash flow and as the basis for applying valuation multiples. For many executives, understanding EBITDA and how it is adjusted is the most practical step toward anticipating how investors will view their business.

This overview reflects material taught in our Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance.

If you’d like a deeper dive into valuation methods and real case studies, you can download the programme brochure here and explore the curriculum in more detail.

How to Calculate EBITDA

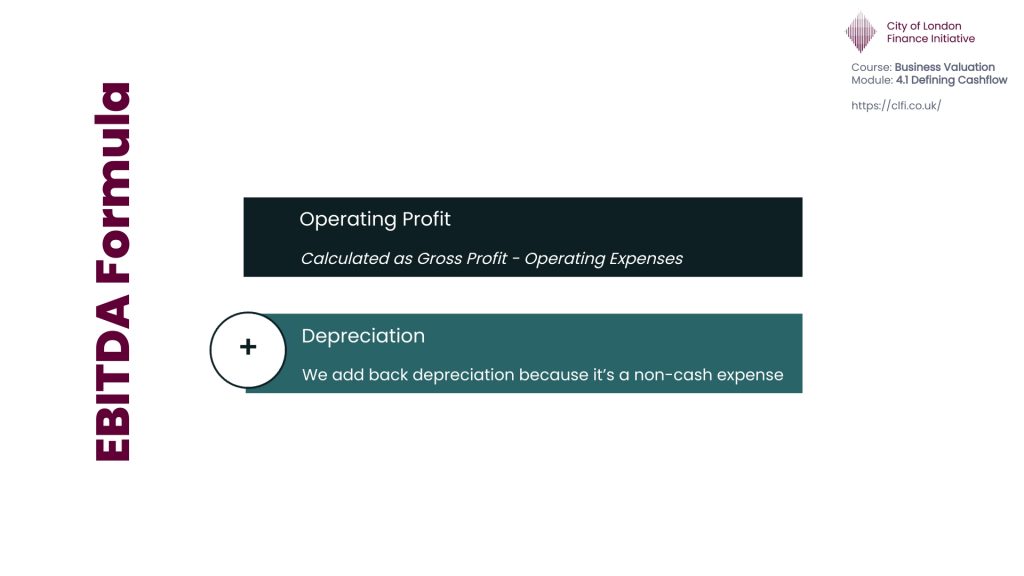

The simplest way to get EBITDA is to start from operating profit (also called EBIT) and add back depreciation and amortisation:

EBITDA = Operating Profit + Depreciation + Amortisation

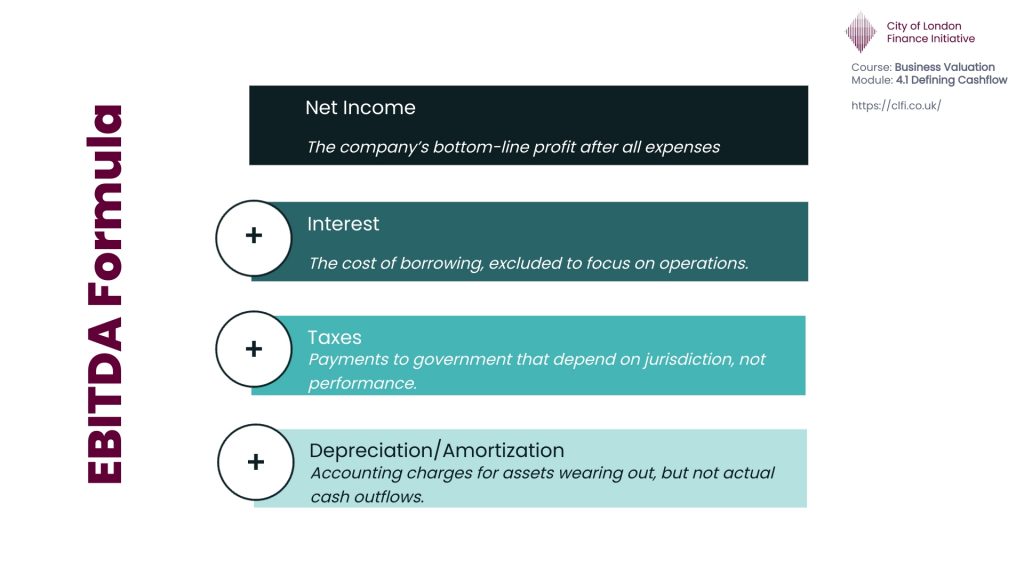

Another way is to start from net income and add back interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation. Both approaches should give the same result if the numbers are consistent.

Why EBITDA Matters? EBITDA strips out financing costs, tax regimes, and non-cash charges to reveal operating performance. For private equity firms conducting leveraged buyouts, it signals whether a company can service debt and still fund growth. Lenders also use EBITDA to set debt covenants, making it central to both acquisition and ongoing monitoring.

Reported EBITDA is rarely accepted at face value. Private equity investors adjust for factors that obscure true operating performance. Common examples include owner-manager salaries that deviate from market rates, personal expenses run through the business, or one-off restructuring and legal costs. These adjustments, known as normalisation, and commonly reported as Adjusted-EBITDA, allow investors to compare companies on a like-for-like basis and focus on the earnings capacity that is sustainable over time.

Valuefinex, an outsourced Fractional CFO Services based in London, commented, «Serving mid-size enterprises across the UK and Europe, we observe that when these businesses are approached by or involved in private equity transactions, valuations most often rely on adjusted EBITDA multiples used in combination with discounted cash flow analysis.»

In addition to normalising the past, investors often project a forward-looking measure known as pro forma EBITDA. This incorporates anticipated synergies, efficiency gains, or revenue enhancements expected after the transaction. While useful in illustrating upside potential, pro forma figures are inherently subjective and must be examined with caution, since they rely on assumptions about integration and execution.

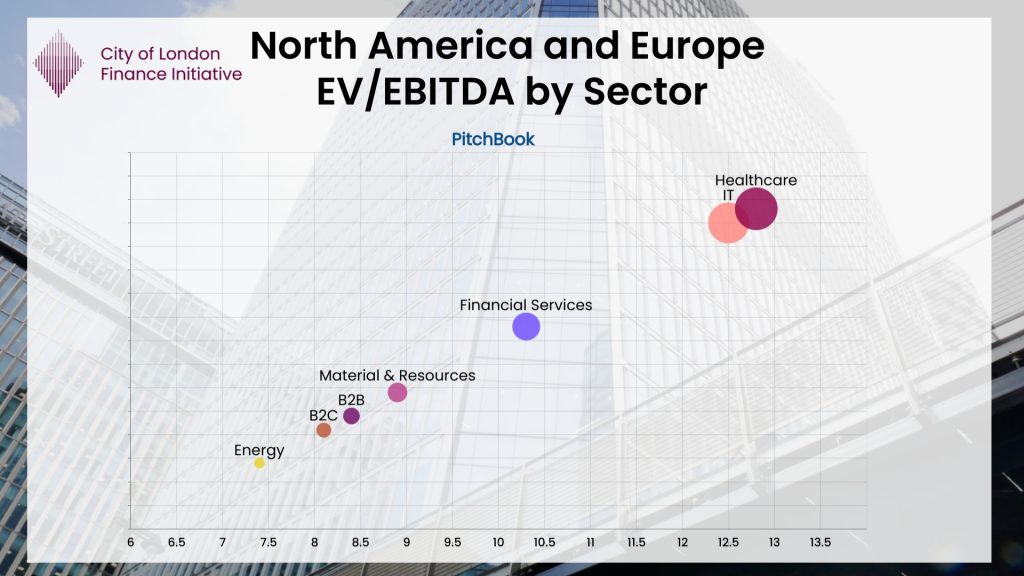

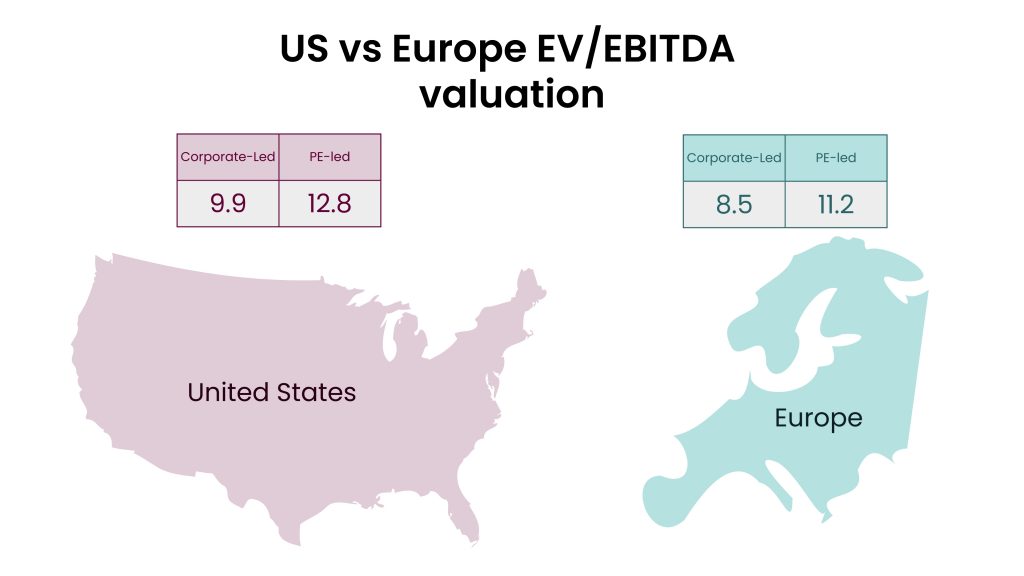

These adjustments matter because private equity valuations are frequently expressed as a multiple of EBITDA, and industry norms differ sharply across sectors. As recent data indicates, and as discussed in our most recent CLFI Insight publication, IT and healthcare businesses in North America and Europe command double-digit median EV/EBITDA multiples, while energy assets trade at far lower levels due to volatility and transition risks. The chart below summarises how sectors compare, providing context for executives preparing for investor discussions.

Looking Forward: Risk, Optimism, Relevance

For CEOs and owners, the valuation process highlights both opportunities and risks. A higher EBITDA multiple can translate directly into a stronger exit value, yet this depends on industry cycles, investor appetite, and macroeconomic factors. For example, technology companies often command double-digit EBITDA multiples, while traditional manufacturing may trade at far lower levels.

Valuations are also highly sensitive to assumptions. Growth forecasts, discount rates, and margin expectations can all swing enterprise value. Executives should therefore focus on presenting credible business plans, with evidence-backed assumptions, to instill confidence. Overly optimistic projections risk undermining credibility during due diligence.

Further adjustments also matter. Illiquidity discounts reflect the fact that private investments cannot be readily sold, often reducing estimated value by 20 to 30 percent. Conversely, control premiums may increase value when investors acquire a majority stake, recognising the influence gained over strategic decisions.

Valuation is not about arriving at a single, definitive number but about establishing a range shaped by data, context, and negotiation. For executives, the task is to understand the levers that drive value — from EBITDA growth and operational efficiency to industry positioning and capital structure — and to use that knowledge to guide investor discussions with realistic expectations. Treated thoughtfully, valuation becomes less a rigid figure and more a guide to how the business is perceived, offering insights into strengths, vulnerabilities, and potential paths to long-term value creation. This perspective equips leaders to approach negotiations with clarity and make strategic choices with greater confidence.

Explore Further from CLFI Insight

References:

- International Private Equity and Venture Capital Valuation Guidelines, IPEV Board, December 2022. IPEV Guidelines

- Valuefinex is a UK-based consulting firm delivering outsourced fractional CFO services to PE-backed firms across the UK and Europe.

- PitchBook, Q2 2025 Global M&A Report. Read more

- Introduction to Private Equity

- What is Corporate Finance?