Table of Contents

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC): Understanding a Company’s Financing Cost

- CLFI Team

- 6 min read

The Weighted Average Cost of Capital, or WACC, is a measure of the average rate of return a company must pay to its investors—both equity holders and lenders—to finance its assets. It reflects the overall cost of capital, weighted by the proportion of debt and equity in the company’s capital structure. WACC is widely used in valuation, investment appraisal, and corporate finance decisions because it represents the minimum return required to justify investment in a business.

The principles underpinning the cost of capital and its role in financing and investment decisions are examined in the Corporate Finance Executive Course.

Table of Contents

- What Is WACC?

- Why WACC Matters

- The WACC Formula

- Cost of Equity

- Cost of Debt

- Worked Example: Calculating WACC

- Limits of WACC

- Further Reading

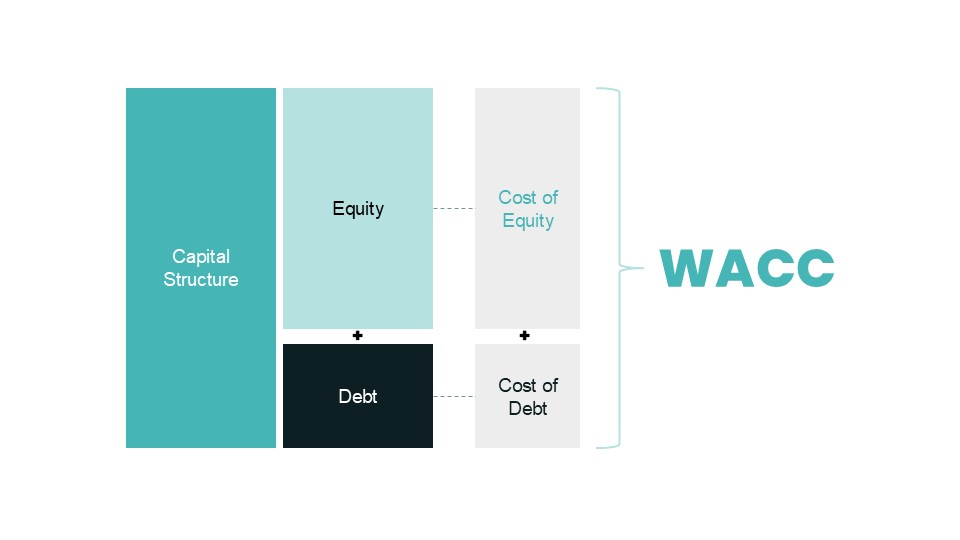

What Is WACC?

WACC is the blended cost of capital from all sources of financing. Companies fund themselves through a mix of equity (shares issued to investors) and debt (borrowed funds such as loans or bonds). Each has a cost: equity investors expect returns in the form of dividends and capital gains, while lenders require interest payments.

Module 4.1 Cost of Capital & WACC

WACC combines these costs in proportion to their weight in the firm’s total financing, giving a single rate that reflects the company’s overall cost of capital.

Why WACC Matters

WACC serves as the “hurdle rate” for investment decisions. If a company’s projects are expected to return more than the WACC, they add value; if they return less, they may destroy value. In valuation models such as Discounted Cash Flow (DCF), WACC is used as the discount rate to calculate the present value of future cash flows. It is also a benchmark for comparing companies: a lower WACC indicates cheaper access to capital, while a higher WACC suggests higher perceived risk or more expensive financing.

The WACC Formula

The general formula is:

WACC = (E/V × Re) + (D/V × Rd × (1 − Tc))

Where:

E = Market value of equity

D = Market value of debt

V = Total firm value (E + D)

Re = Cost of equity

Rd = Cost of debt

Tc = Corporate tax rate

The tax shield (1 − Tc) reflects that interest payments are tax deductible, reducing the effective cost of debt.

Cost of Equity

The cost of equity (Re) is the return required by shareholders to compensate for risk. It is often estimated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), which links the cost of equity to the risk-free rate, market risk premium, and the company’s beta (a measure of stock volatility). Equity is usually the more expensive source of capital, as investors require higher returns than lenders.

Cost of Debt

The cost of debt (Rd) is the effective interest rate a company pays on borrowed funds. Because interest is tax-deductible, the after-tax cost of debt is lower than the nominal rate. For example, if a company pays 7.5% interest on loans and faces a corporate tax rate of 35%, the after-tax cost of debt is 7.5% × (1 − 0.35) = 4.9%.

Worked Example: Calculating WACC

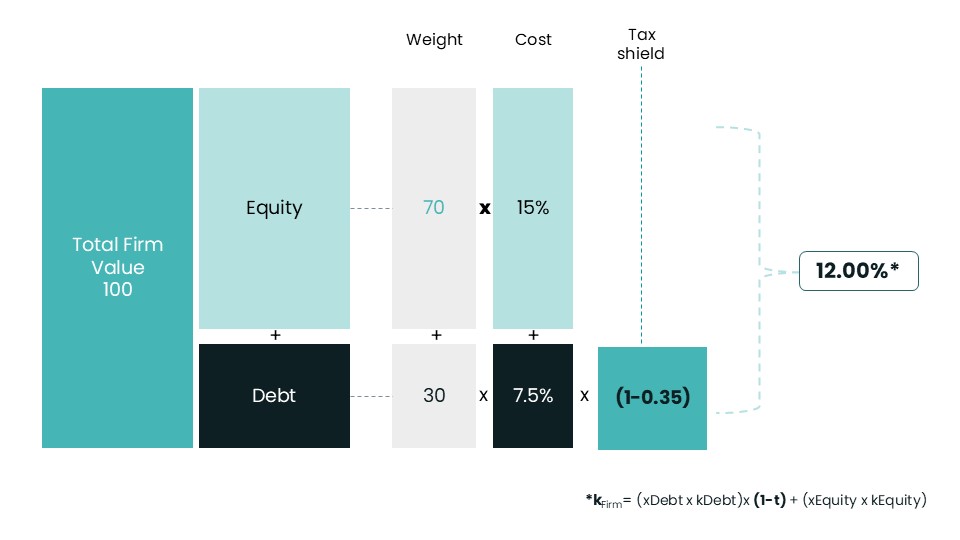

Consider a company with the following structure:

Total Firm Value: 100

Equity: 70 (70%)

Debt: 30 (30%)

Cost of Equity (Re): 15%

Cost of Debt (Rd): 7.5%

Corporate Tax Rate (Tc): 35%

Module 4.1 Cost of Capital & WACC

Applying the formula:

WACC = (70/100 × 15%) + (30/100 × 7.5% × (1 − 0.35))

WACC = (10.5%) + (1.5%)

WACC = 12.0%

This means the company must earn at least 12% on its investments to satisfy both debt holders and equity investors.

Limits of WACC

WACC is a useful benchmark but has limitations. It assumes the company’s capital structure remains constant, which may not hold in practice. Estimating the cost of equity via CAPM depends on market assumptions that can change quickly. WACC may also be misleading if applied to projects with different risk profiles than the overall firm. For these reasons, analysts often adjust WACC for specific business units or projects to reflect different levels of risk.

Capital Is a Resource. Allocation Is a Strategy.

Learn more through the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance – a structured programme integrating governance, finance, valuation, and strategy.

Learn How to Calculate WACC in the Real World

As part of the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance – WACC is addressed from both a financing and valuation perspective. Its foundations are developed in the Corporate Finance course, while its practical application as a discount rate is worked through in the Business Valuation course, using guided exercises and real-world case material.

Across the modules, you will:

- Estimate Re using CAPM, selecting an appropriate risk-free curve and constructing a market risk premium.

- Calculate Rd from bond yields or loan margins and convert it to after-tax terms using the applicable corporate tax rate.

- Apply market value weights rather than book values and reconcile them to enterprise value for consistency in discounted cash flow analysis.

- Use WACC correctly within a Discounted Cash Flow model.

- Address practical considerations including country risk premia, inflation (nominal versus real WACC), minority interests, leases, and diversified businesses with differing risk profiles.

By the end, you will be able to compute a defensible WACC, articulate the underlying assumptions in boardroom terms, and use it appropriately both as a discount rate for valuation and as a hurdle rate in capital budgeting decisions.

WACC — Comparisons and Common Questions

This section clarifies how WACC relates to closely associated concepts including CAPM, DCF, discount rates, and IRR, using concise explanations aligned with professional valuation practice.

WACC and CAPM — how do they relate?

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) is used to estimate the cost of equity (Re), one of the key inputs in WACC. CAPM links expected equity returns to the risk-free rate, market risk premium, and company beta. The resulting cost of equity is then combined with the cost of debt to calculate the firm’s weighted average cost of capital.

WACC and DCF — which discount rate should be used?

In a discounted cash flow model, WACC is used to discount Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF), producing enterprise value. When valuing Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE), the appropriate discount rate is the cost of equity. If leverage is expected to change materially, practitioners often apply the adjusted present value (APV) framework instead.

WACC vs discount rate — are they the same?

WACC is one form of discount rate, reflecting the blended cost of debt and equity for a firm as a whole. However, not all discount rates are WACC. Project-specific or equity-only cash flows require discount rates adjusted to their own risk characteristics.

WACC vs IRR — how are they used together?

Internal Rate of Return (IRR) measures the return generated by a project’s cash flows, while WACC represents the minimum required return given the firm’s risk and capital structure. If IRR exceeds WACC, the project creates value. For projects with higher-than-average risk, the hurdle rate should be adjusted upward before comparison.

How to match cash flows and discount rates

Consistency rule:

- Free Cash Flow to the Firm → discount at WACC → enterprise value

- Free Cash Flow to Equity → discount at cost of equity → equity value

Learn more in the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance.