Table of Contents

How Are Private Equity Fees Structured?

- CLFI Team

- 5 min read

Private equity fund fees are more than just numbers on a term sheet — they shape how value is shared between investors and fund managers. They determine how General Partners (GPs) are paid, how Limited Partners (LPs) measure their net returns, and how incentives align over the fund’s life. For LPs, fee terms influence the decision to commit capital; for GPs, they define whether running the fund is commercially viable. This guide takes you through the core elements of private equity fee structures — from fixed management fees to performance-linked carried interest — and the evolving negotiation trends shaping the market.

The principles governing how private equity funds structure fees and align incentives between General and Limited Partners are examined in the Private Equity Executive Course.

Table of Contents

- Management Fees

- Carried Interest

- Monitoring and Transaction Fees

- Preferred Return and Hurdle Rate

- Fee Transparency and LP Negotiation Trends

Management Fees

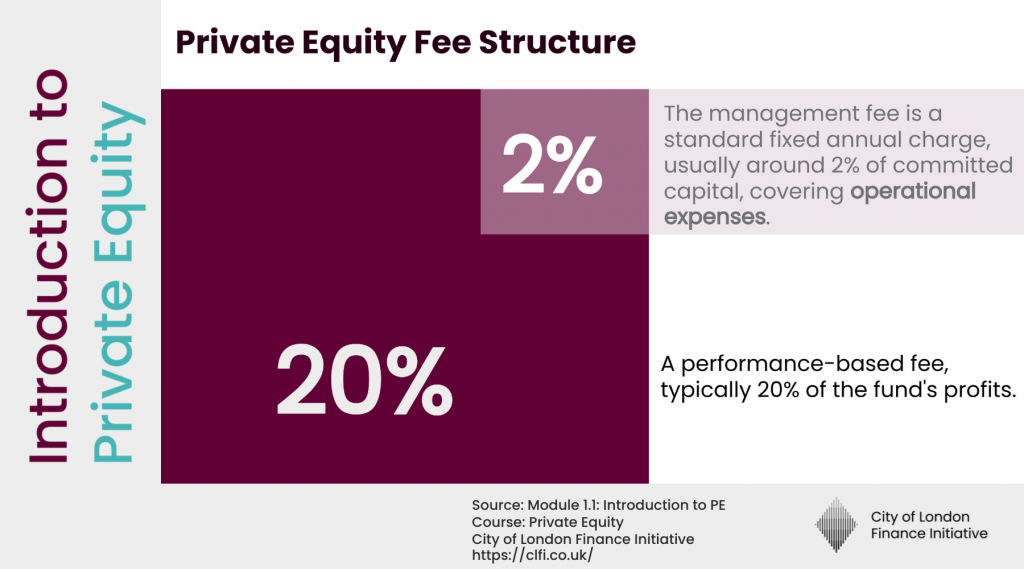

Management fees provide the fixed-income foundation of a private equity fund’s revenue model. Paid by LPs to the GP, they cover the operational cost of running the fund — from paying investment team salaries to funding deal sourcing, compliance, and reporting. Typically, they are charged as a percentage of committed capital during the investment period, most often between 1.5% and 2% for mid-market funds. Larger funds often secure lower rates thanks to economies of scale.

Fee calculation methods vary. Some funds apply a constant rate over the fund’s life, while others use a decreasing schedule. A common structure is to shift the basis from committed capital to invested capital after the investment period, ensuring fees better reflect assets actively under management. Hybrid models may combine both approaches.

Most funds apply a five-year investment period, after which a “step-down” occurs. E.g. fees are reduced (often by 25% or more) and calculated on invested capital. This keeps costs proportionate to the GP’s ongoing workload as the portfolio matures.

Over-reliance on management fees can create tension. In years with weak performance, GPs may depend heavily on these fees, potentially blurring alignment with LPs. As a result, sophisticated LPs push for structures that fairly compensate GPs while keeping incentives tied to value creation.

Example: A fund with £250 million in commitments at a 2% fee generates £5 million annually during the investment period. Once the step-down applies and £200 million remains invested, a reduced 1.5% fee would yield £3 million — reflecting the reduced level of active portfolio management.

Carried Interest

Management fees pay for the day-to-day operations, while carried interest — often called “carry” — is the GP’s share of the profits for strong performance. It is the GP’s agreed share of fund profits, typically 20% (sometimes up to 25%), earned only when returns exceed a defined performance threshold. Its design ensures that GPs are rewarded for creating value beyond the minimum expected by LPs.

Programme Content Overview

The Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance delivers a full business-school-standard curriculum through flexible, self-paced modules. It covers five integrated courses — Corporate Finance, Business Valuation, Corporate Governance, Private Equity, and Mergers & Acquisitions — each contributing a defined share of the overall learning experience, combining academic depth with practical application.

Chart: Percentage weighting of each core course within the CLFI Executive Certificate curriculum.

Capital Is a Resource. Allocation Is a Strategy.

Learn more through the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance – a structured programme integrating governance, finance, valuation, and strategy.

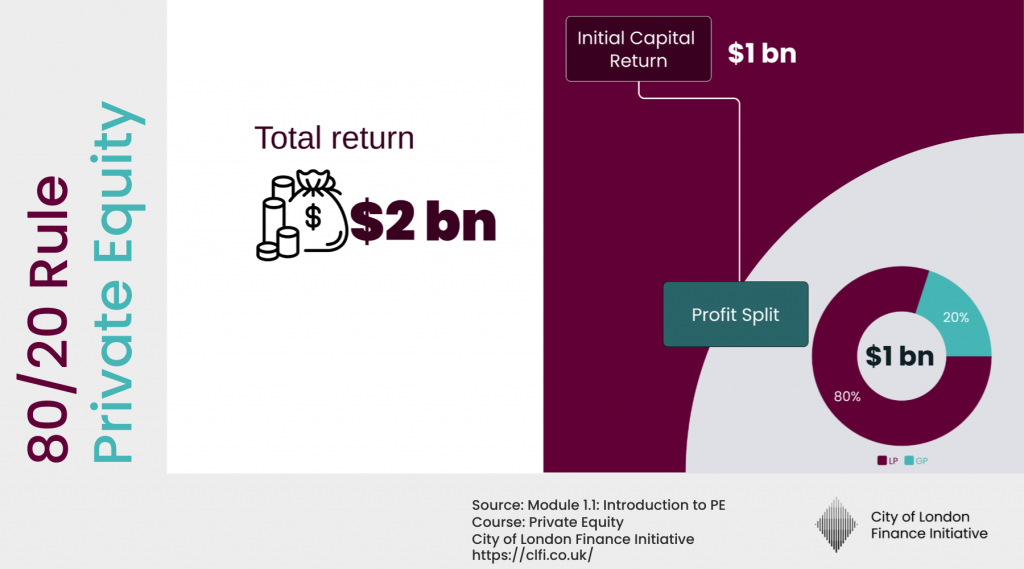

Let’s say a private equity fund raised $1.5 billion from LPs. Over the life of the fund, the investments generate $4 billion in total proceeds.

-

Return of Capital: The first $1.5 billion goes straight back to LPs, repaying their initial investment.

-

Preferred Return: Next, LPs receive their agreed annual preferred return — for example, 8% per year on the capital they committed. This ensures they are compensated for the time value and risk of their investment before any profit sharing begins.

-

Profit Eligible for Carry: After the preferred return is met, the remaining amount is considered profit to be split between LPs and the General Partner (GP). Let’s assume that in this example, that leaves $2 billion in eligible profit.

-

Carry Split: With a standard 20% carried interest rate, the GP receives $400 million (20% of $2 billion), and the remaining $1.6 billion goes to the LPs.

This sequence ensures GPs are rewarded only after LPs have fully recovered their capital and earned a baseline return, keeping incentives aligned.

There are two main ways carry is paid. In the “whole-of-fund” approach, common in Europe, GPs get their share of profits only after the entire fund clears the hurdle rate. In the “deal-by-deal” approach, more common in the U.S., GPs can take carry from each winning deal as it’s sold — which pays them sooner but can cause problems if later deals lose money.

Some funds let GPs “catch up” on their share of profits once investors have received their minimum return, so the GP quickly gets to their agreed percentage. A “clawback” rule means that if the fund’s final results don’t meet expectations, the GP must pay back any extra profits they took earlier.

Monitoring and Transaction Fees

In addition to the fees paid by investors, GPs often charge portfolio companies for certain services. Monitoring fees are ongoing charges for advice, board involvement, and overseeing operations. Transaction fees are one-time charges during a company’s purchase or sale to cover deal work and structuring. Monitoring fees are usually a fixed amount or a small percentage of the company’s EBITDA, while transaction fees are often 1%–2% of the deal value. To prevent GPs from being paid twice for the same work, investors (LPs) often require a fee offset. This means any fees collected from portfolio companies are deducted from the management fees paid by LPs. In most developed markets, a full (100%) offset is now standard.Preferred Return and Hurdle Rate

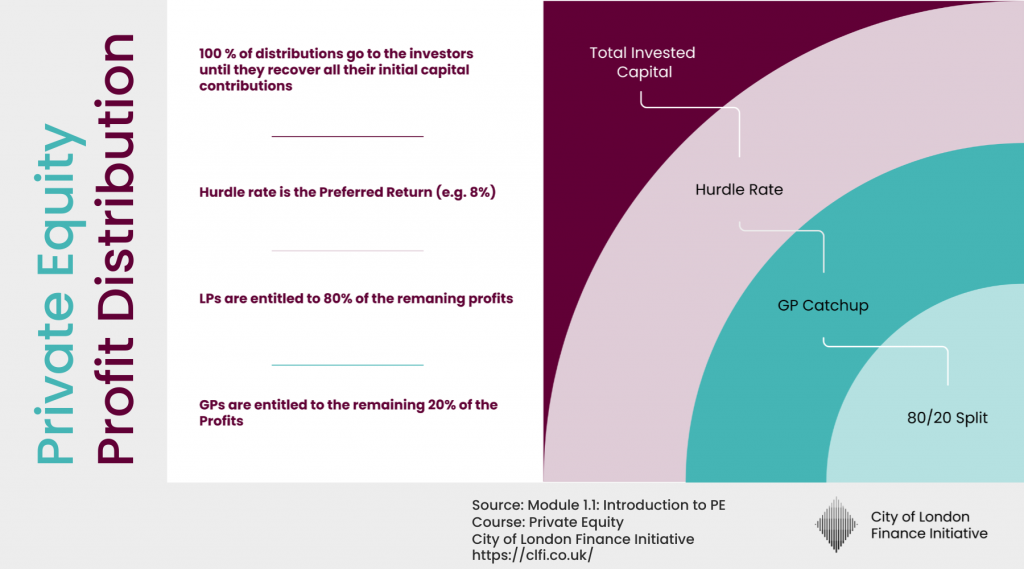

The preferred return and hurdle rate are LP-first safeguards and GP performance targets. The preferred return — typically 8% per annum, compounded — is the minimum LPs must earn before GPs receive carry. The hurdle rate is the point above which profit-sharing begins; in most cases, the two terms are used interchangeably.

To decide who gets paid and in what order, private equity funds use what’s called a “waterfall” distribution (see infographic below). First, LPs receive back all the capital they originally invested. Second, they receive their preferred return. Only after these steps are complete does the GP become eligible for carried interest, which is usually set at 20% of the remaining profits.

Example: In a $1 billion fund generating a total return of $2 billion, LPs first receive back their $1 billion investment. The remaining $1 billion profit is split according to the agreed carry terms — typically 80% to LPs and 20% to GPs — resulting in $800 million for LPs and $200 million for GPs.

Fee Transparency and LP Negotiation Trends

Fee terms have become a focal point in fundraising negotiations. Institutional LPs increasingly demand lower post-investment management fees, stricter definitions of allowable expenses, and caps on transaction charges. The Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA) has also standardised reporting templates, giving LPs greater visibility into fee and expense allocations.

ESG-linked carry, performance-linked fee adjustments, and enhanced disclosure are shaping the next generation of fund agreements — reinforcing the need for GPs to balance commercial sustainability with transparency and LP trust.