Table of Contents

What Is EBITDA and what's its relevance?

- CLFI Team

- 6 min read

EBITDA is one of those finance terms widely used in company reports, investment pitches, and news articles about businesses. It stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortisation. EBITDA provides a view of how much profit a company generates from its underlying business activities, before the impact of financing choices, tax regimes, or accounting charges related to the gradual use of assets. In this article, we set out what EBITDA represents, why it is widely used in financial analysis, how it is calculated in practice, and the limitations to bear in mind when relying on it.

The role of EBITDA as an analytical measure, and its distinction from cash flow and accounting income, is examined within the Business Valuation Executive Course.

Table of Contents

- What Is EBITDA?

- Why EBITDA Matters

- Breaking Down the Parts of EBITDA

- How to Calculate EBITDA

- Worked Example: EBITDA in Practice

- Common Adjustments to EBITDA

- Limits of EBITDA

- Further Reading

What Is EBITDA?

EBITDA is commonly used as an indicator of a company’s operating performance. It removes the effects of financing decisions (interest), differences in tax regimes (taxes), and accounting charges for the gradual consumption of assets (depreciation and amortisation). The result is a clearer picture of earnings generated by the company’s core operations. While it is often viewed as a proxy for “cash profit from operations,” it is not the same as actual cash flow.

Why EBITDA Matters

EBITDA has become a popular shortcut for comparing companies. Investors use it to judge profitability across industries and borders, because it removes differences in tax rates and financing. Lenders use it to test whether borrowers can service debt, often by setting covenants such as “Debt/EBITDA must stay below 3.” Companies highlight it in presentations because it often shows a cleaner, sometimes stronger, picture of performance than net income. Journalists and analysts use it in valuation multiples like EV/EBITDA to say what price investors are paying for each unit of profit.

Breaking Down the Parts of EBITDA

Each element of EBITDA reflects an adjustment made on the way from revenue to net profit:

- Earnings: Refers to operating profit, often called EBIT. It begins with revenue and deducts routine operating costs such as wages, materials, and utilities.

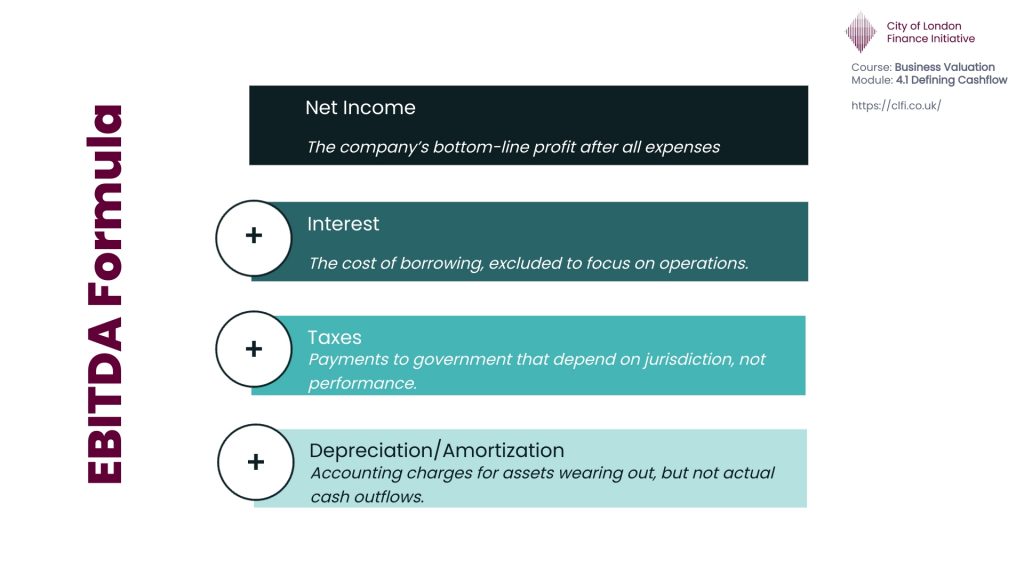

- Interest: Represents the cost of borrowing. EBITDA excludes this to allow comparison between companies regardless of their capital structure.

- Taxes: Corporate tax charges vary by jurisdiction. By removing them, EBITDA highlights performance before the impact of local tax policy.

- Depreciation: A non-cash expense that allocates the cost of tangible assets such as buildings, machinery, and vehicles over their useful lives.

- Amortisation: Similar in concept to depreciation, but applied to intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, and acquired goodwill.

By excluding interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation, EBITDA isolates the profitability of a company’s core business operations. This is why in business valuation domain, this is also known as the closest metric to Free Cash Flow.

How to Calculate EBITDA

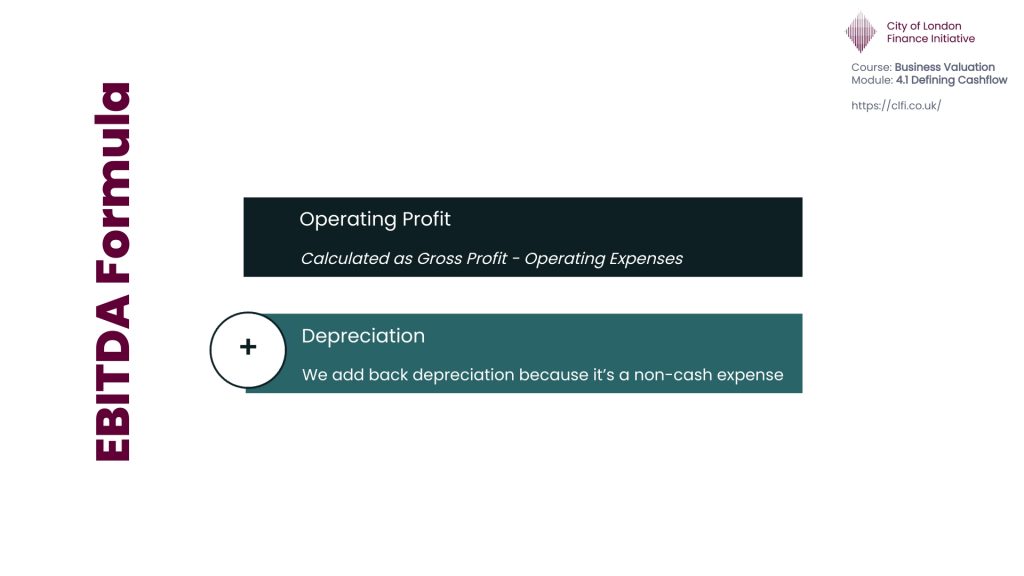

The simplest way to get EBITDA is to start from operating profit (also called EBIT) and add back depreciation and amortisation:

EBITDA = Operating Profit + Depreciation + Amortisation

Source: CLFI

Another way is to start from net income and add back interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation. Both approaches should give the same result if the numbers are consistent.

Source: CLFI

Price Is a Data Point. Value Is a Decision.

Learn more through the Executive Certificate in Corporate Finance, Valuation & Governance – a structured programme integrating governance, finance, valuation, and strategy.

Worked Example: EBITDA in Practice

Understanding how EBITDA relates to Net Income through a step-by-step calculation.

Suppose a company has the following annual results (in £ millions). We'll calculate both Net Income and EBITDA to show how these two key metrics relate to each other.

| Revenue | £1,000 |

| Operating costs (excluding depreciation) | £700 |

| Depreciation | £50 |

| Amortisation | £20 |

| Interest expense | £30 |

| Taxes | £60 |

Calculate Net Income

Start from revenue and work down through all expenses to arrive at the bottom-line profit figure.

| Line Item | Amount (£m) |

|---|---|

| Revenue | £1,000 |

| Less: Operating costs (excluding depreciation) | (£700) |

| Less: Depreciation | (£50) |

| Less: Amortisation | (£20) |

| = Operating Profit (EBIT) | £230 |

| Less: Interest expense | (£30) |

| Less: Taxes | (£60) |

| = Net Income | £140 |

Net Income of £140 million represents the final profit after all expenses, including interest and taxes, have been deducted.

Calculate EBITDA

To calculate EBITDA, we take EBIT (Operating Profit) and add back the non-cash charges: depreciation and amortisation.

| Line Item | Amount (£m) |

|---|---|

| Operating Profit (EBIT) | £230 |

| Add back: Depreciation | £50 |

| Add back: Amortisation | £20 |

| = EBITDA | £300 |

EBITDA of £300 million shows the company's earnings before accounting for non-cash charges (depreciation and amortisation), interest, and taxes. It provides a clearer view of operational cash-generating ability.

Learning Takeaway

This example demonstrates the relationship between Net Income and EBITDA:

Common Adjustments to EBITDA

Not all EBITDA numbers are the same. Companies often report “adjusted EBITDA,” adding back items they argue are unusual or one-off, such as restructuring costs, legal settlements, or write-downs. Sometimes this makes sense, as removing non-recurring costs can show a clearer picture of ongoing performance. Other times, it can make results look artificially strong. Analysts often read the fine print to see what has been adjusted and whether it is justified.

Limits of EBITDA

EBITDA is useful, but it is not perfect. It is not the same as cash flow, because it ignores changes in working capital and capital expenditures (money spent on new equipment or buildings). It can also hide high interest costs or heavy tax burdens that affect the bottom line. For asset-heavy industries such as airlines or utilities, depreciation is a real and recurring cost. Ignoring it can paint too rosy a picture. This is why professional analysts always look at EBITDA alongside other measures, such as operating cash flow and net income.

A further limitation is the widespread use of adjusted EBITDA in company reports. Because EBITDA is not a formally defined accounting measure, businesses often modify it to exclude costs they consider unusual or non-recurring. The outcome is that each company effectively creates its own version of EBITDA, which undermines comparability and consistency.

Example — WeWork’s Adjusted EBITDA

A well-known case was WeWork’s use of “Community Adjusted EBITDA,” where it added back not only non-cash charges but also routine expenses such as marketing. This transformed significant losses into what appeared to be positive operating results.

WeWork’s subsequent collapse, under Adam Neumann’s management, underscored the dangers: its unsustainable growth model, reckless leadership, and failed IPO in 2019 revealed losses that no adjustment could conceal.

Such practices highlight the risk. While adjustments may be justified in specific circumstances, aggressive add-backs can distort reality and present a more favourable picture than the underlying performance warrants.